Translate this page into:

Cure in onychomycosis: A multifaceted and evolving concept

*Corresponding author: Chander Grover, Department of Dermatology and Sexually Transmitted Diseases, University College of Medical Sciences, and Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, New Delhi, India chandergroverkubba76@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Gaurav V, Grover C. Cure in onychomycosis: A multifaceted and evolving concept. J Onychol Nail Surg. 2025;2:1-3. doi: 10.25259/JONS_7_2025

Onychomycosis is a prevalent and persistent fungal infection of the nails that has perplexed both clinicians and researchers due to its complex pathophysiology and the challenges associated with achieving a definitive cure. Despite significant advancements in antifungal therapies, the term ‘cure’ in onychomycosis remains ambiguous, leading to varying interpretations in clinical practice and research. The multifaceted concept of ‘cure’ in onychomycosis remains a subject of ongoing debate, with persistent controversies in the literature.[1,2]

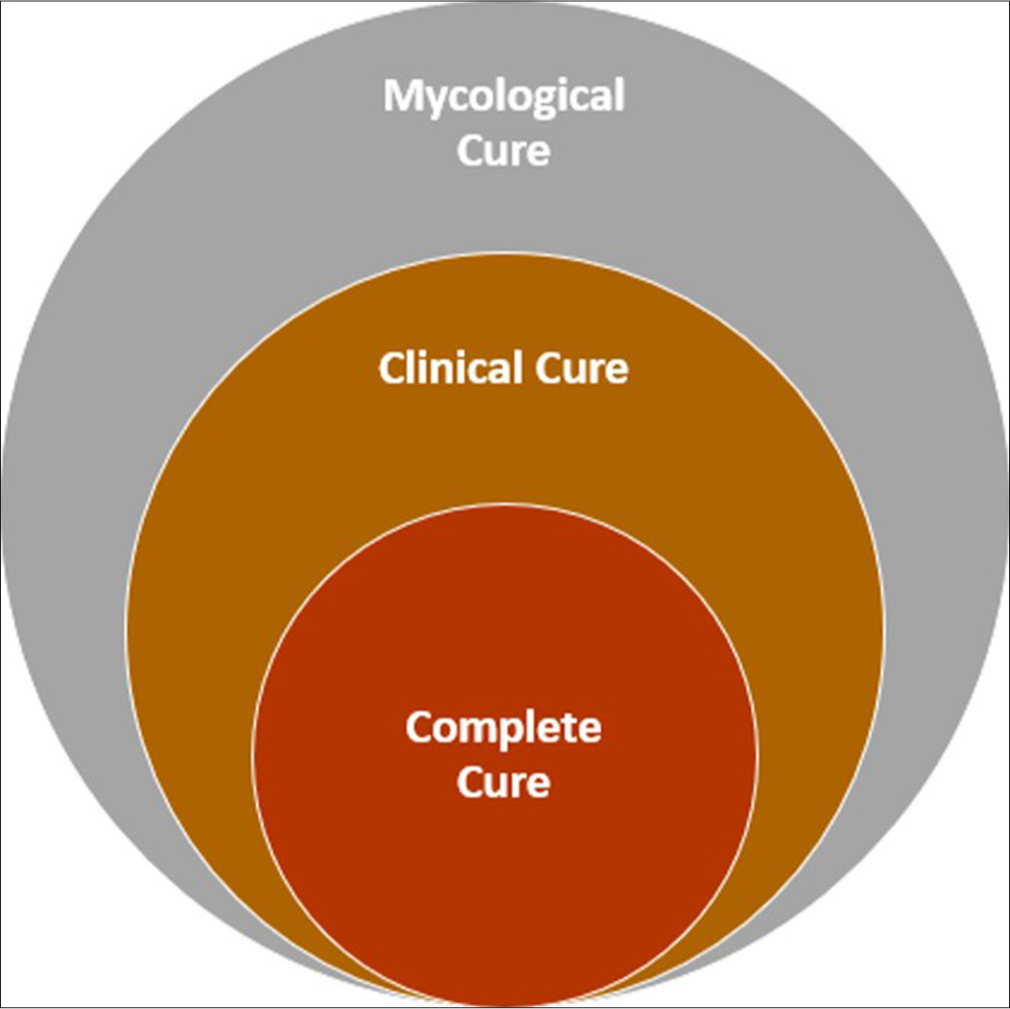

The concept of ‘cure’ in onychomycosis is generally understood through two primary lenses: Mycological cure and clinical cure [Figure 1]. Mycological cure is defined by the eradication of the fungal pathogen from the nail and surrounding tissues, typically confirmed through negative potassium hydroxide (KOH) microscopy and culture. On the other hand, clinical cure pertains to the visible resolution of infection, characterised by the restoration of a normal-appearing nail plate.[1,3]

- Venn diagram showing the nested definitions of cure: Illustrating the relationship between complete, clinical and mycological cure.

However, the literature reveals that these definitions are not always aligned. For instance, a patient may achieve mycological cure without a corresponding clinical cure due to residual nail damage or slow nail regrowth. Conversely, a nail may appear clinically normal, but the underlying fungal infection may persist, raising the risk of recurrence. This discordance between mycological and clinical outcomes complicates the assessment of treatment efficacy and the interpretation of clinical trial results.[4]

Achieving a mycological cure is considered the gold standard in the treatment of onychomycosis, as it is the most reliable indicator of pathogen eradication and a predictor of long-term success. However, mycological cure alone is insufficient if the nail does not regain its normal appearance, as patient satisfaction and quality of life are closely tied to the visual outcomes of treatment.[1,4]

The definition of mycological cure is also subject to variation, with some studies requiring both negative culture and microscopy, while others rely solely on culture results. This variability in diagnostic criteria can lead to inconsistent outcomes in clinical trials, making it difficult to compare the efficacy of different treatments. Moreover, the persistence of dead fungal elements in the nail, detectable by microscopy, may not necessarily indicate active infection, further complicating the assessment of cure.[1-4]

While clinical cure is crucial for patient satisfaction, it is inherently subjective and influenced by various factors beyond the eradication of the fungal pathogen. Nail appearance can be affected by prior damage, comorbid conditions and external factors such as trauma, making it a less reliable indicator of true cure. In addition, the slow growth rate of nails means that even after successful treatment, it may take several months for a clinically abnormal nail to fully grow out, during which time the risk of recurrence remains.[1,4]

To address these limitations, expanded definitions of cure have been proposed to capture partial improvements and meaningful clinical outcomes [Figure 2]:

- Hierarchy of clinical outcomes: From clinical improvement to complete cure.

Complete cure: Defined as the combination of both mycological and clinical cure, is the ultimate goal in the treatment of onychomycosis. However, achieving complete cure is challenging, with rates varying widely depending on the severity of the infection, the type of antifungal treatment used and patient adherence to therapy.[1]

Almost complete cure: Defined as ≤5% or ≤10% clinical involvement and mycological cure. This definition acknowledges that complete resolution may not always be achievable, but a significant reduction in clinical symptoms combined with pathogen eradication can still be considered a successful outcome. It is particularly relevant in cases where minor residual lesions persist despite effective treatment.[4-9]

Clinical success: Defined as having <10% of the nail affected compared to the baseline involvement, along with evidence of normal nail growth. Mycological status is not necessarily negative. This measure is useful for assessing treatment progress, even if full cure is not achieved. It allows for the evaluation of partial improvements, which may still provide meaningful benefits to patients, particularly in severe cases of onychomycosis.[4-9] It should ideally be assessed at least 48 weeks after initiation of therapy. This time frame allows for near-complete nail outgrowth and resolution of visible changes, though minor adjustments may be needed depending on whether fingernails or toenails are involved.

Clinical effectiveness: It is defined as the combination of mycological cure (negative KOH microscopy and culture) and outgrowth of healthy nail, typically requiring at least 3–5 mm of new, unaffected nail growth. This measure is clinically relevant as it offers a comprehensive assessment of therapeutic success, integrating both microbiological eradication and visible clinical improvement.[5,6]

Clinical improvement: Refers to a reduction in the total affected nail area by more than 20% compared to baseline. This definition is necessary to capture cases where the treatment has led to significant improvement, though not complete resolution. Clinical improvement is an important outcome for patients who may not achieve full cure but experience a substantial reduction in symptoms and disease burden.[4-9] It can be evaluated at interim checkpoints such as 12, 24 or 36 weeks to monitor therapeutic progress. Continued follow-up is recommended to confirm sustained improvement over time.

In clinical practice, the focus is often on the great toenail as the target for evaluating cure, given its size and susceptibility to infection. However, this approach may overlook the outcomes in other affected nails, leading to an incomplete assessment of treatment success. Moreover, the great toenail is particularly prone to trauma, which can result in permanent deformities and lower complete cure rates compared to other toenails.[1,8] Therefore, a more comprehensive assessment that considers all affected nails and potential confounding factors is warranted. Despite the progress in understanding onychomycosis, the current definitions of cure remain inadequate to capture the complexity of outcomes observed in clinical practice. To refine the concept of cure and guide future research, the following recommendations are proposed:

Standardise definitions across clinical trials: Future studies should adopt standardised definitions of mycological and clinical cure to ensure consistency and facilitate comparison of treatment outcomes. Uniform diagnostic criteria, including the requirement for both negative culture and microscopy, should be emphasised to improve the reliability of mycological assessment.

Onychoscopy as a tool for standardised cure assessment: While onychoscopy has gained attention as a valuable non-invasive tool for the diagnosis of onychomycosis, particularly in differentiating it from other causes of nail dystrophy, its role in assessing treatment response or defining cure remains largely unexplored. At present, there is a lack of published data supporting the use of onychoscopy for monitoring therapeutic outcomes or documenting resolution of disease. Given its ability to visualise subtle changes in nail morphology and the proximal nail bed, onychoscopy could potentially offer a more objective and earlier indication of treatment response when compared to gross clinical inspection alone. Future prospective studies are warranted to evaluate whether serial onychoscopic examinations can reliably reflect disease activity, correlate with mycological outcomes and thereby contribute to a more nuanced and non-invasive definition of cure in onychomycosis.

Incorporate long-term outcomes and recurrence rates: Clinical trials should incorporate long-term follow-up data to evaluate recurrence rates and durability of cure. A complete assessment of outcomes should include both mycological and clinical cure, as well as patient-reported outcomes to capture real-world effectiveness.

Evaluate adjunctive measures and combination therapies: Given the challenges in achieving complete cure, future research should explore the efficacy of adjunctive therapies such as nail debridement, laser therapy and topical antifungal combinations in enhancing clinical outcomes. Combination approaches that address both pathogen eradication and nail regeneration may offer a more comprehensive solution to treatment.

Define patient-centred outcomes: Patient satisfaction, quality of life and reduction in symptom burden should be prioritised as key outcomes in clinical trials. Studies should explore the correlation between visual improvement and patient-reported satisfaction to better align research outcomes with patient expectations.

In clinical practice, the goal should be to aspire for ‘functional cure’ – a state where the nail shows substantial clinical improvement, even if not fully restored to its pre-infection state, combined with sustained mycological eradication to minimise recurrence. This approach acknowledges that complete cure may not always be achievable, especially in patients with extensive nail involvement or comorbidities affecting nail regrowth.[1,9] Therefore, clinical success and almost complete cure should be considered acceptable endpoints in such cases, providing meaningful symptomatic relief and improving quality of life. Clinicians should also engage in shared decision-making with patients, setting realistic expectations regarding outcomes and emphasising the importance of post-treatment maintenance and preventive measures.

Moreover, future research should prioritise identifying biomarkers or surrogate markers that can predict long-term treatment success, facilitating earlier intervention and personalised therapeutic strategies. Investigating host factors such as immune response, nail growth kinetics and genetic predisposition may provide valuable insights into individual variability in treatment outcomes. In addition, incorporating artificial intelligence-assisted image analysis in clinical trials could enhance the objectivity of clinical cure assessment and standardise evaluation across studies.[10]

To drive meaningful change in practice, it is imperative to shift the focus of clinical trials and treatment guidelines toward more pragmatic and patient-centred outcomes. Incorporating quality of life measures and reduction in symptom burden as primary endpoints of therapy, will better align treatment goals with patient expectations. In addition, guidelines should advocate for a more flexible definition of cure that accounts for the realities of clinical practice, where partial improvement often constitutes a meaningful outcome. By aligning future research and clinical practice with these goals, we can move closer to achieving consistent, durable and patient-centred success in the treatment of onychomycosis.

References

- Onychomycosis: Diagnosis and definition of cure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:939-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updated perspectives on the diagnosis and management of onychomycosis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:1933-57.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The problems with our current definition of cure in onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:AB117.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Goals for the treatment of onychomycosis In: Baran R, Haneke E, Hay R, Tosti A, Richert-Baran B, eds. Fungal infections of the nail and scalp: The current approach to diagnosis and therapy (3rd ed). United States: CRC Press; 2024. p. :79-85.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- How do we measure efficacy of therapy in onychomycosis: Patient, physician, and regulatory perspectives. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:498-504.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onychomycosis: Does cure equate to treatment success? J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:626-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nail society of India (NSI) recommendations for pharmacologic therapy of onychomycosis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2023;14:330-41.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efinaconazole in the treatment of onychomycosis. Infect Drug Resist. 2015;8:163-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artificial intelligence in diagnosis and management of nail disorders: A narrative review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2024;16:40-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]